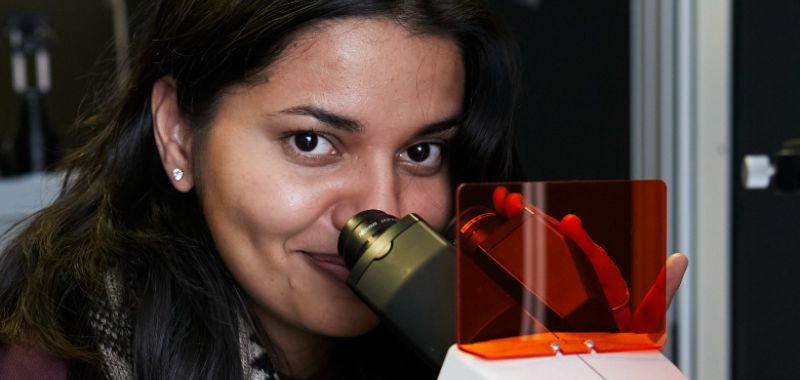

Member profile: Anchal Yadav

From a crash course in chemistry to becoming a new mother amid COVID-19, the route to a PhD was far from simple for Anchal Yadav.

But taking the road less travelled – and overcoming countless obstacles along the way - has transformed the Monash University Research Fellow from a shy student into one of the most resilient, determined members of Exciton Science.

Anchal’s PhD specialised in synthesising hybrid nanostructures for use as self-assembly building blocks in more efficient solar cells.

And like so many of her colleagues, it was childhood curiosity that set her on the path to a career in research.

Early curiosity

“I think I was always into science,” she said.

“I never desired a career in history or politics. I was curious as to why light bulbs glow. At school, the teacher tells you the fundamentals, but you may not always understand the full tale or the science behind it. I used to watch the Discovery Channel to learn more about it. I wanted to learn how the world works.”

Now a member of Chief Investigator Alison Funston’s Nanoscale Spectroscopy Laboratory, Anchal completed an undergraduate degree in Physics and a master’s in Nanotechnology in her native India, and then quickly got to grips with the challenges posed by a PhD in a different field.

“To be honest, I am a physicist,” she said.

“I did my bachelor’s, my master’s, everything in physics. Chemistry was new to me and so is the synthesis world but having a great supervisor by your side during that time makes everything so much easier.”

“I began my PhD with little knowledge of basic chemistry, yet the process of learning has transformed me into a completely different person. I've learned a lot about it since then.”

PhD, parenting and pandemic

While most students understandably experience considerable stress during the process of completing their PhD, for Anchal those challenges were amplified by a happy but enormously demanding major life event.

“I got married during my PhD,” she said.

“And then another life-changing event happened – pregnancy. I was working with toxic chemicals, so I had to put everything on hold to protect my unborn child. I had to stop everything because I could not work with them.

“But because I was in my final year, I started working on my thesis. However, that was when I got hit by the initial phase of pregnancy - extreme morning sickness. Looking at the situation, I decided to travel to India to deliver the baby."

“The pregnancy was difficult, as was the postpartum period. I had to rush through an emergency C-section and the newborn was born critically ill."

“After all of our difficulties, we returned to begin a normal life and to finish my PhD. That's when COVID started. We were in lockdown. My husband lost his job during COVID and I wasn’t fully recovered from the surgery. I couldn't resume my PhD and I was going through my financial hardship.

“But, my supervisor was there! Even though I was on maternity leave, we used to have online meetings and she kept checking on me to see if I was okay and needed any help. She tried her best to help me financially and emotionally.”

Anchal (front right) is pictured with past and present members of Alison Funston's research group. Alison is on the far left.

Anchal (front right) is pictured with past and present members of Alison Funston's research group. Alison is on the far left.

Highlighting the need for positive change

Anchal’s experience highlights the need for greater flexibility from universities and the research sector to handle multiple systematic challenges, including extended leave and absence allowance for students, better provision of financial support during extenuating circumstances, access to subsidised childcare, and rectifying the disparity in treatment between international and domestic students, as well as between men and women.

Addressing just one such challenge, she said: “Particularly for women who've had children, we need longer postdoc roles, even if it’s part-time and spread over four years, not two or three.”

Thankfully, Anchal was able to access counselling services through Monash University to help her cope.

She feels many elements of the research system are favourable, but called for greater engagement with international students, and more understanding of the challenges they face navigating an unfamiliar structure while being far away from their typical support mechanisms.

“I think Australia is very friendly,” she said.

“The environment, the culture, the research work, the way it is designed, is very good.

“It's good that we have these (mental health) programs where we can communicate with someone, we can meet with people and talk about things.

“But as I said, being an international student, it's very difficult. You are dealing with a lot of problems that only a few people can understand. There are language barriers, financial barriers, and the anguish of being separated from friends and family. And you have to meet the criteria of being a good student.”

Equipped to overcome any obstacle

Having survived such a challenging experience, Anchal is now justifiably proud of her achievements, which have equipped her not just with scientific expertise, but also valuable communication skills and a determination to forge a career path in which the importance of her family will be recognised and celebrated.

“I'm not a (naturally) sociable person,” she said.

“But this journey has made me stronger academically, socially and emotionally. I am much more confident than I was.”

“A postdoc, like any other job, is tough. However, this is an excellent opportunity to hone your skills and maximise the chances of pursuing a career as an independent scientist.

“It will help me widen my horizons by acquiring skills in a new area, or possibly a new topic, that complements my PhD research. I also admire how adaptable it is in terms of family management. The abilities I'll acquire here may also aid me in transitioning from academia to industry in the future.”

For now, we’re grateful to have Anchal as a member of the Centre, with her unique skills and remarkable life experience making a demonstrable contribution to Exciton Science.